The Secret History of Wonder Woman 2014, Jill Lepore. 410 pages, hardcover. (7 out of 10 stars)

This is a book I’ve been excited about for some time. Even though everyone knows Marvel’s Stan Lee, and comic book fanboys know Superman’s Siegel and Schuster and Batman’s Bob Kane and Bill Finger…Wonder Woman’s creator has been more of an enigma. Jill Lepore has finally broken that enigma open in an excellent biography of William Moulton Marston in “The Secret History of Wonder Woman.”

I heard Lepore interviewed on NPR a month or so before I picked up the book, so I knew what to expect with the book. Not an overview of Wonder Woman’s publishing history, not a fictionalized biography of the Amazing Amazon, but a biography of the writer who created her, and what inspired him to do so. As a longtime DC Comics nerd, but also as a history teacher and one who already knew enough about Marston to be dangerous, I was excited to read the book.

William Moulton Marston was a bigamist.

While Wonder Woman always had a secret identity of Diana Prince in the comic books—until relatively recently at least—the bigger secret was the life and lifestyle of her creator. Because William Moulton Marston was a bigamist. His first wife was Sadie Elizabeth Holloway, with whom he had two children—his second was Olive Byrne, with whom he also had two children and who lived in the same home and mothered side-by-side with Holloway. Another woman lived in the same home, but seemed to be more of a live-in aide than an actual wife, and it’s not clear there were any shenanigans between Marston and her. In any case, the guy had multiple wives. What’s more intriguing to me is that, unlike the traditional views on polygamy in the United States, Marston seems to have been motivated to take multiple wives because he admired women and elevated them so much.

The first several chapters of the book aren’t focused on Marston at all, but on the women’s suffrage movement, and on the work of Margaret Sanger, most famous for promoting birth control and the eventual birth control pill. All of this groundwork will come into fruition with its influence on Wonder Woman later, but there’s also a direct connection to Marston’s life because Byrne was Sanger’s niece.

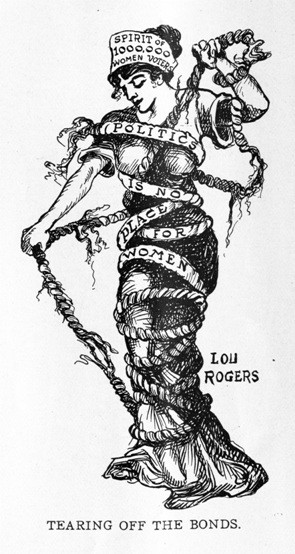

Lepore looks at the ways the suffragettes shaped the ideals of Wonder Woman – an island of women ruling themselves without men, who can have power and influence over men when they enter into our world. She also pulls out examples of other novels and plays where there are similar gynotopias (I think I just made up that word, but I like it) to Paradise Island, and how they may have influenced the creation of Wonder Woman. Even the look of Wonder Woman was influenced by the suffragists, with political cartoons featuring women breaking out of chains becoming a central image in Wonder Woman comic books.

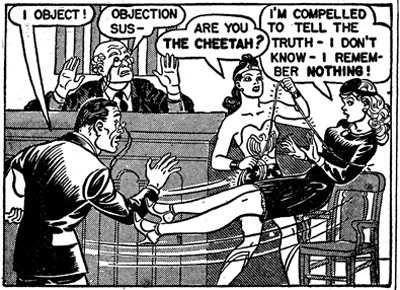

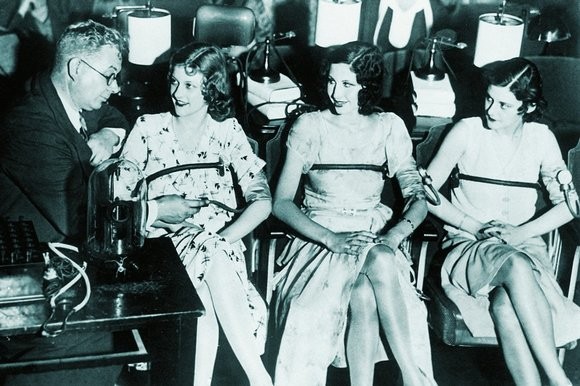

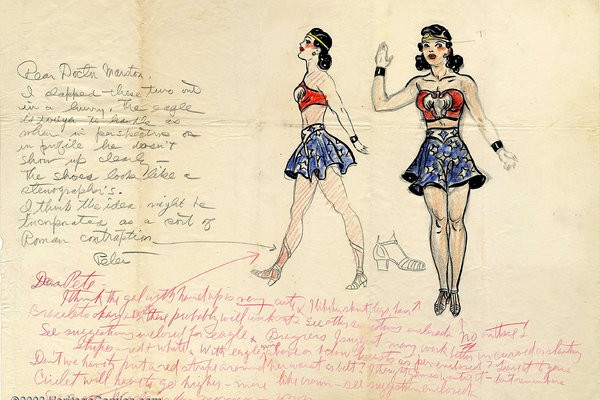

Marston was a psychologist who proclaimed himself the inventor of the lie detector test—which (ironically) is stretching the truth a little. He did a lot of experiments using the device, he honed it, he used it a lot in his own research…but it was more that he was a ceaseless promoter of the polygraph than that he actually invented it. That was something I already knew, and knew that it influenced Wonder Woman’s “lasso of truth,” but it was still interesting to read about it here. Lepore writes a fascinating biography that gets at the bizarre core of a man who was into bondage, who put that into comic books, but who also had an admiration for women. He mandated a “Wonder Women of History” feature in every book—a two-page biography on Susan B. Anthony or Margaret Sanger or Marie Curie or other notable women of the real world. He made sure Wonder Woman was always more powerful than the men in the book, and had settings like all-female schools and colleges where the brilliance of women would be celebrated.

…a man who was into bondage…but still had a sincere admiration for women

Lepore uses panels and covers from 1940s comics to illustrate the book, along with photos and political cartoons from the 1890s on. There are family photos of the Marston family that haven’t been published before, and the first sketches for how Wonder Woman might look, and images that influenced her design.

I loved this book, but I do have two problems with it. And they’re kind of a big deal. First is that the book is titled “The Secret History of Wonder Woman,” it has Diana Prince changing into Wonder Woman on the cover, but it gives relatively short shrift to the superheroing itself. It’s all behind-the-scenes stuff that doesn’t really get into the impact of the character in the comic book world. He does point out that she’s one of only three heroes that survived the purge of superhero comics spearheaded by Frederic Wertham. He mentions in a few paragraphs that she was part of the Justice Society. But within the fictional DC Universe, she became part of a trinity of heroes. She’s been in nearly every incarnation of the Justice League. She’s depicted as having strength only second to (often equal to) Superman. Every female superhero since 1941 has been subordinate to her, but that fictional history that’s lasted over seven decades isn’t given much credit. I know that it’s not the point of the book, but by ignoring it completely, she’s doing fans who are picking up the book because of Wonder Woman (in the title, on the cover) a disservice.

The second problem I have with it—and this is huge, this blew my mind, it actually offended me—is that the Wonder Woman that many of us grew up with, the one who inspired girls and boys on playgrounds across the country and around the world—warrants only a paragraph. Lynda Carter, who still, nearly forty years later is the touchstone for fans, is only mentioned once. And it’s a fairly derisive mention. For a historian like Lepore, who has spent so much time researching the character and the history, to dismiss what for us is the reason we started reading comics in the first place…it hurt. There’s one paragraph about the development of the television series, one paragraph quoting the lyrics to the theme song, and one paragraph that mentions that Lynda Carter was a Miss America pageant winner.

Lepore’s treatment of Lynda Carter nearly undoes all the goodwill I had towards this book

And that’s it. Over 400 pages about Wonder Woman, and this gets less than a page? Lepore implies that the 1970s series undid all of the feminist progress that Wonder Woman had made in comic books and pop culture in the previous decades. I heartily disagree. That program showed a strong, independent, smart woman who completely kicked ass. She was beautiful. Don’t get me wrong, I still have a schoolboy crush on her. But she was the female superhero that we all looked up to. Until the X-Men and Avengers movies, she was one of the few successful runs of a superhero on the big or small screen, and she’s as much of an icon as Christopher Reeve’s Superman, and for the same reasons. She was the essence of the character. For as dated as the series is by today’s standards, she still shines as brightly as she did when I was a pup. And Lepore’s treatment of her undid almost all of the goodwill I had for this book.

It’s a stunning biography. It’s an insightful look at the creation of a superhero that will last into the lives of my grandchildren and great-grandchildren. But it also took a huge part of that character’s impact and pushed it aside for its own agenda. I still recommend reading it, but be ready for a painful ending.