In my longtime tenure as a Mass Effect fan, I’ve often envisioned the conversation that took place between creators Casey Hudson and Drew Karpyshyn after they wrapped up their wildly successful Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic franchise. They had just created two of the best Star Wars games of all time, and their unfiltered access to the LucasArts library had no doubt left them with more than a few fascinating ideas.

I imagine them speaking back and forth about what made their work with KOTOR so special, until Hudson simply says, “You know what? We could do that. We could do Star Wars with our own planets, aliens, characters—” at which point Karpyshyn holds up a finger and asks, “These characters—can they bang each other?” Hudson simply smiles and nods his head. At this point in my dramatization, both Hudson and Karpyshyn leap into the air for a high five as an explosion of stars and rainbows erupts behind them.

It’s been ten years since the first Mass Effect game was released on the Xbox 360, and now, BioWare is bringing players back to the Mass Effect universe just like Bill Paxton (may he rest in peace) brought Rose back to Titanic. The next chapter is Mass Effect: Andromeda, and it’s scheduled for release on March 21 on PS4, Xbox One, and PC. Whether you’re new to the franchise or a full-fledged N7 operative, join me here each week to get psyched up for Andromeda with some nostalgic rehashing of the greatest video game trilogy of all time.

Mass Effect 1: Rise of the Intergalactic Underdogs

From the get go, Mass Effect reached out and extended a brave middle finger to the sci-fi video game tropes that had bogged down the genre for decades. Mass Effect is refreshingly free from roided out ex-cons with improbable size proportions (Gears of War), faceless supermen that exist only to gun down everything in their path (Halo) and female characters that are fetishized as prizes to be ogled after a hard day of testosterone-drenched slaughter (pretty much every game ever). Instead, we got one of the few truly cinematic gaming experiences of the Xbox 360’s life cycle—not to mention the fact that players from all walks of life can find something relatable in Mass Effect’s operatic, character-driven story.

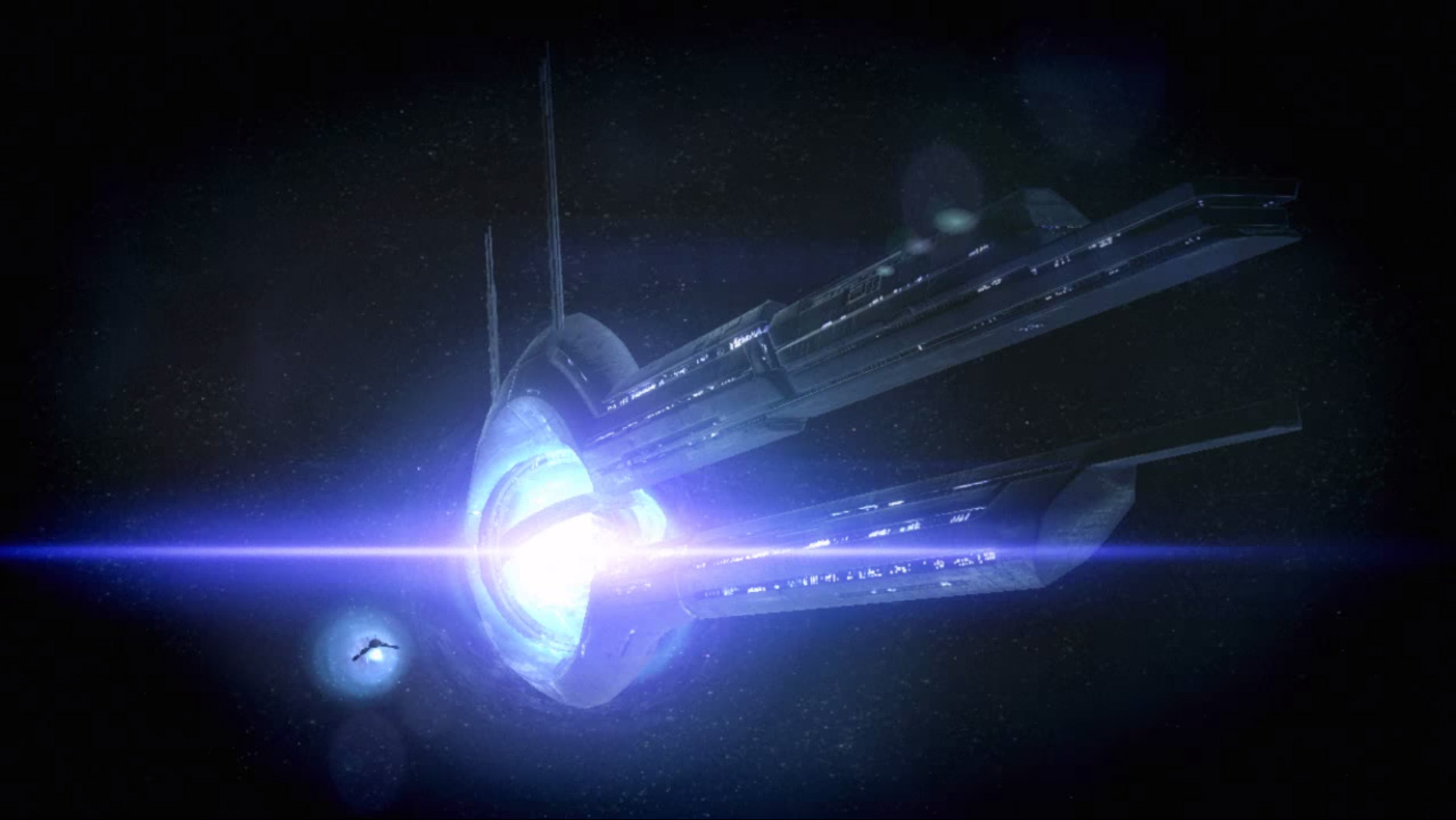

In the opening moments of 2007’s Mass Effect, we learn that humanity has discovered giant, transdimensional gateways called Mass Relays, which manipulate space and time to transport ships from one point of the galaxy to another—they end up calling this process mass effect. Through the use of the Mass Relays, humanity learns that there is a bigger galaxy out there—one that has been operating just fine on its own, completely unaware that human beings were a thing.

The game takes place just after humanity is granted an embassy on the Citadel, which is the intergalactic hub of politics and culture. At best, the galaxy’s political powers consider humanity to be a bunch of impulsive upstarts, at worst, they don’t consider them at all. The player takes control of Shepard (who can be generated as a male or female character), a proficient operative in the human-controlled Earth Systems Alliance. The Citadel Council offers Shepard a spot with the Spectres, special operatives that work on behalf of the Council. As the first human to ever join the Spectres, Shepard becomes a symbol of humanity’s ascendance in the political ranks of the galaxy.

Shepard’s first assignment is to track down and arrest Saren, a rogue Specter who is actually little more than a puppet to an even more dastardly evil out beyond the stars. Along the way, Shepard recruits a diverse roster of intergalactic outcasts, and their relationships—romantic or otherwise—span the life of the trilogy. Throughout the series, the team’s primary struggle is to prevent the invasion of the Reapers, giant, sentient warships that exterminate organic life every 50,000 years. On paper, it sounds pretty generic, but it’s all just an elaborate backdrop for what is essentially a character-focused drama.

Mass Effect’s treatment of the human race is unique to most sci-fi tales. The game casts humanity itself as an intergalactic underdog, which perfectly sets the stage for Shepard’s work as a Spectre. When the Council shrugs off Shepard’s knowledge of the Reaper invasion, it’s completely believable. After all, humans are still sitting at the political kiddie table with the squat, mouth-breathing Volus and the emotionless, quadrupedal Elcor. Shepard’s dialogue options come heavily weighted with racial tension, giving the player the choice between tolerance and isolationism with nearly every conversation. This dichotomy helps create a close relationship among the player, Shepard and humanity. Every victory we make as a Spectre counts as one more thing that humans are doing right—but it’s ultimately your choice as to whether you want to be a dick about it.

Even though going back and playing through Mass Effect now is a janky experience—all the human characters appear to have perpetual walleye vision, and I do not miss the loot management system—it remains a fantastic entry point into the universe that Hudson and Karpyshyn have created.

Next week: Mass Effect 2, the alt-right and hot, narrative-driving sex.